Tags

ghostbusters, monologue, play, Playwriting, process, soliloquy

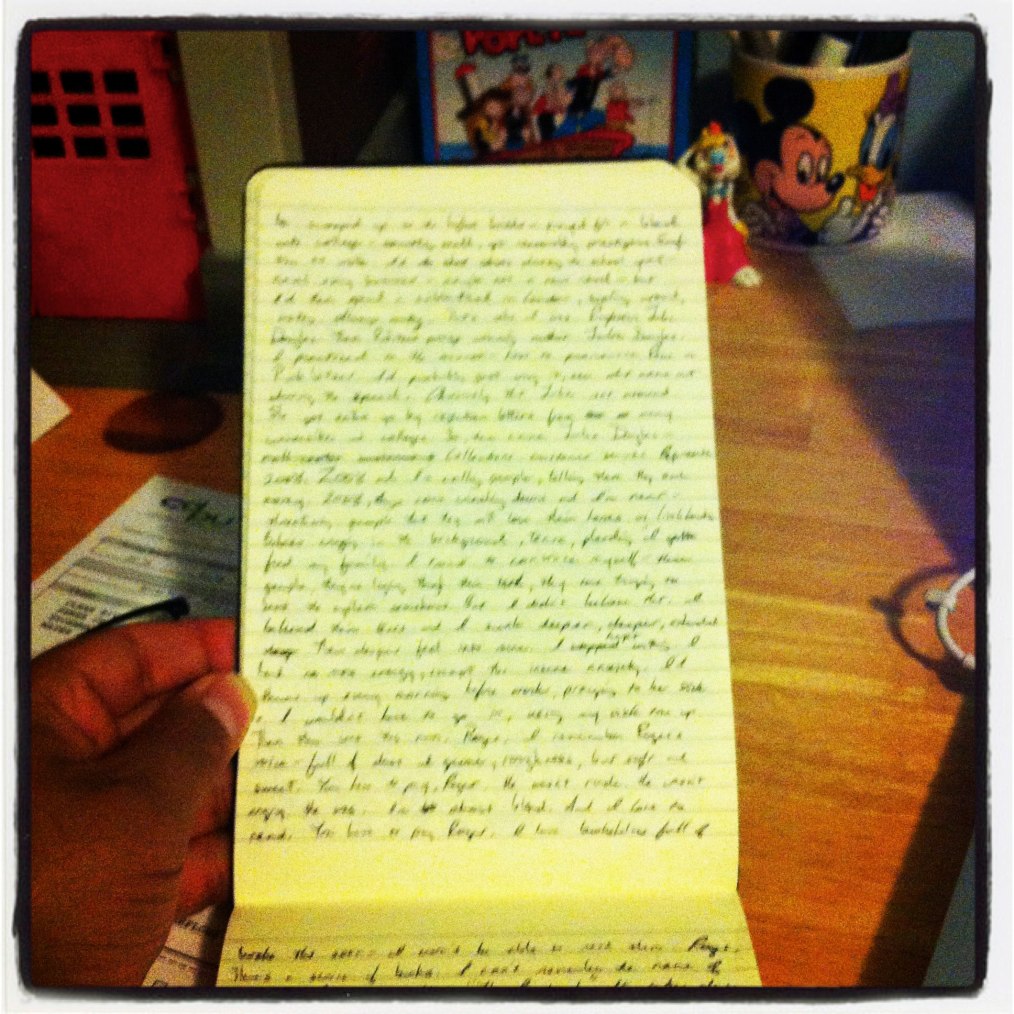

In writing my newest play, Books & Bridges, I’ve come to the point at which a character has a massive turning point, perhaps the turning point for her, and I’ve found myself wondering: “Is this a monologue?” I don’t say soliloquy because she’s speaking to other people, but it’s a big, ol’ monologue. It takes up the better part of 3 1/2 pages in my Moleskine. I don’t know what that translates to in “proper” script formatting, but I imagine it’s long.

Now, I realize it’s nowhere near the length of the 20-some page monologue that is the first act of Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul. nor is it the rolling escapade that is Hickey’s monologue in Act 4 of The Iceman Cometh. It aligns itself somewhere in between Aston’s revelation in Pinter’s The Caretaker and Belinsky’s outpouring in Stoppard’s The Coast of Utopia: Voyage.

I’ve written many a monologue in my day, but have always struggled with the question: am I writing scaffolding or meat? The scaffolding is often what you write when you’re just trying to get things out, those moments when the subtext is not “sub” at all, hearts are firmly on sleeves, and dialogue feels heavy-handed and heavy-footed as well. It’s not that it’s bad writing necessarily, but it’s bad drama. If left to its own devices.

However, the key is seeing the scaffolding for what it is and digging into it to find the meat, which means hacking quite a lot, slicing here and there, making a general mess of the lumbering mass that was, in your mind, holding the play up. But it wasn’t. The play stands without it. It was a necessary step towards getting the play written (by any means). I know that I’ve written plenty of scaffolding in my plays. Here’s one of the worst from my play All Grace. A priest is speaking directly to the audience.:

You are about to take part in a sacred ritual. In fact, the ritual has already started. Before these lights around us dimmed, before you entered this place, before you arrived, before you left your home or office, you were preparing to come. That preparation was the start of this beautiful ritual. I, myself, was preparing. I made sure my robes were in order, my glasses clear of debris. I cleared my voice, knowing that I would be addressing you this evening and hoping that in my clarity of voice, I would also, somehow, be able to present a clarity of thought. But let me tell you this. As you participate in this ritual. Do not think. For, in art, it is not the intellect that judges and discriminates, it is the senses. Tonight, you must use the intuition of your senses and not of your reason. Already many of you are questioning, “Do not think? What does he mean? Art? Reason? Sacred ritual? What is the meaning of this?” We must quiet those restless minds of yours.

It goes on and on from there. Curious to read the rest of it? Be my guest. But surely you’ve gotten the idea. Bad. But necessary because I didn’t know the character, I didn’t know his desires, his wants, definitely not his voice. This scaffolding monologue answered most of these questions for me. I mean, it was the first words I wrote for the play, so please be lenient in your judgements.

So, now I’m sitting here, my 2 1/2 Moleskine page monologue sitting next to me, wondering have I written meat or scaffolding? It’s not a question I can answer now. Ask me after this draft of the play is finished. I might have an answer.

Also, unrelated because I’m sure you’re curious. Yes. That is the Ghostbusters’ firehouse living on my desk.